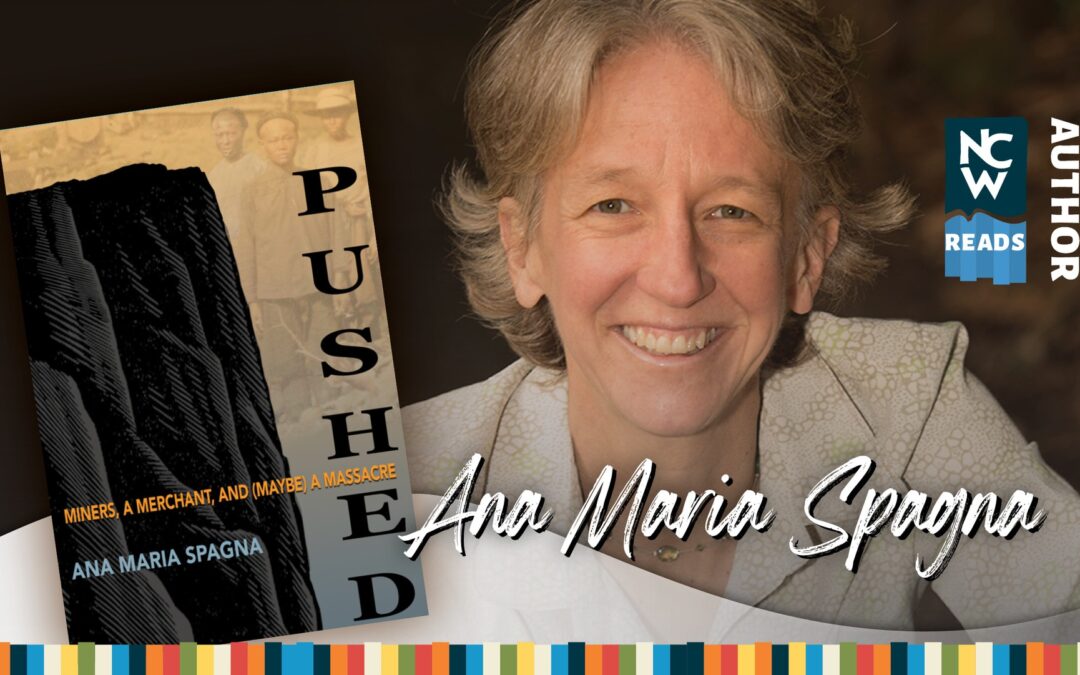

Join us for a conversation with Stehekin-based author Ana Maria Spagna as she shares her latest book Pushed: Miners, a Merchant, and (Maybe) a Massacre, in which she explores a little-known incident dubbed the Chelan Falls Massacre.

NCW Libraries is offering two opportunities to hear Spagna talk in September:

- Virtual: Sept 7, 7 p.m., via the Zoom platform REGISTER

- In-Person: Sept. 8, 4:30 p.m., at Wenatchee Public Library

Spagna is the author of nine books. Her work has been recognized by the River Teeth Literary Nonfiction Prize, the Society for Environmental Journalists, the Nautilus Book Awards, and as a four-time finalist for the Washington State Book Award. A former backcountry trails worker, Ana Maria now teaches in MFA programs at Antioch University, Los Angeles, and Western Colorado University.

For her latest book, Spagna stumbled upon a story: one day in 1875, according to lore, on a high bluff over the Columbia River, a group of local Indigenous people murdered a large number of Chinese miners –perhaps as many as three hundred– and pushed their bodies over a cliff into the river. The little-known incident was dubbed the Chelan Falls Massacre. Despite having lived in the area for more than thirty years, Spagna had never before heard of this event. She set out to discover exactly what happened and why.

For her latest book, Spagna stumbled upon a story: one day in 1875, according to lore, on a high bluff over the Columbia River, a group of local Indigenous people murdered a large number of Chinese miners –perhaps as many as three hundred– and pushed their bodies over a cliff into the river. The little-known incident was dubbed the Chelan Falls Massacre. Despite having lived in the area for more than thirty years, Spagna had never before heard of this event. She set out to discover exactly what happened and why.

Consulting historians, archaeologists, Indigenous elders, and even a grave dowser, Spagna uncovers three possible versions of the event: Native people as perpetrators. White people as perpetrators. It didn’t happen at all. Pushed: Miners, a Merchant, and (Maybe) a Massacre replaces convenient narratives of the American West with nuance and complexity, revealing the danger in forgetting or remembering atrocities when history is murky and asking what allegiance to a place requires.

Spagna recently answered some questions we posed to her about how she discovered the story, what she’s up to now, and what she’ll be talking about in her program.

How did you come up with the idea for this story?

I originally found a mention of the Chelan Falls Massacre in a book titled Wapato Heritage: The History of Chelan and Entiat Indians by Tom Hackenmiller. Later, I began to see mentions regularly: in the museum at Rocky Reach Dam, in books about the region like The Way I Heard It: A Three-Nation Reading Vacation by Arnie Marchand, then in more scholarly sources about the history of the Chinese in the region, and I was intrigued. I didn’t even know the role Chinese immigrants had planned in our region.

How did you carry out the research on this story with so many possible ways it happened?

Every possible way! I spent a lot of time in archives at Whitman College, at the Spokane Public Library, at the Wing Luke Museum in Seattle. I also traveled around to regional historical museums and societies in Chelan, Okanogan, Oroville and Pateros. There I met people who shared my interest and together we explored the story, in writing and on the land. Finally, I had to do a lot of work understanding the larger context: studying Chinese immigration and policy in the West, as well as immigration generally. One very useful book was America for Americans by Erika Lee. Another was The Chinese Must Go by Beth Lew-Williams.

NCW Libraries was crucial, as always! (In Stehekin we are dependent on the mail order library — such a great resource). Librarians found one crucial book from 1904, An Illustrated History of Stevens, Ferry, Okanogan, and Chelan Counties by Richard Steele, and sent the wonderful huge old volume to me.

Did you ever conclusively find out what happened? How do you represent history when you don’t know for sure?

I hate to give away the ending of the book. I discovered many possible credible versions of the story … but no, I did not reach one firm conclusion. The book includes as many versions as I could find, using all of the many sources I discovered. For example, the Wenatchee Museum has copies of the ledger from Miller’s Store that shows the names of many Chinese customers up until 1875, when the massacre supposedly occurred. Then there are none for a few years. This suggests that *something* happened. So, I take that information and speculate. Maybe this happened? Or maybe this? What about the 1872 earthquake? Was that part of the equation? It’s very important to me to tell all of these versions as nonfiction, even if they are not conclusive. It feels crucial to me that people know that something happened, that we have facts, even if they are meager. It would be a different kind of project to take those facts and make-up one story, as historical fiction, but then I would be the “decider” of what’s true. I’d rather be the person opening the door to the truth, murky as it may be, urging readers to make their own conclusions.

Is it better to erase events from history or misrepresent what happened?

Such a difficult question, one I thought about every day while writing. Neither erasing nor misrepresenting history is good. What I think happens with stories like this one, about marginalized or under-represented people, is that our fear of getting the story wrong keeps us from writing or telling the stories at all. So we effectively erase their history. These are people who didn’t write their stories because of language barriers or fear of persecution or who maybe *did* write them down only to have them lost or destroyed. If we only believe the histories that were written and have been preserved, we only get the stories of the powerful. That’s a terribly small sliver of history, and a skewed version to boot.

What is your connection to NCW? Are all your books based in Washington?

What is your connection to NCW? Are all your books based in Washington?

I’ve lived in Stehekin for over thirty years. (Though in recent years, I left for part-time teaching jobs — at Whitman College, the University of Montana, and St. Lawrence University. I’ve just accepted a position at Wenatchee Valley College, so I’ll be staying closer to home.) I’ve written nine books, and all are set, at least partly, in the state. My three essay collections, in particular Potluck, Now Go Home, and Uplake, are firmly set in and around Stehekin. My young adult novel, The Luckiest Scar on Earth, about a 14 year-old snowboarder, is set in a fictional town on the east side of the mountains with both apple orchards and a ski area, and a previous nonfiction book, Reclaimers, focuses in part on Rocky Reach Dam.

What are you working on now?

The book I’m working on right now is a series of stories inspired by encounters with animals — fishers, sea lions, swans, snakes. It’s still brewing, so I can’t say much more about it, but it’s been fun to think about our connections to the nonhuman world.

What are you reading now?

I just finished The Sentence by Louise Erdrich and loved it. Another recent favorite novel was Stay & Fight by Madeline ffitch. In the nonfiction realm, I am thoroughly enjoying Inciting Joy by Ross Gay. (I love all of Ross Gay’s writing and am eagerly looking forward to the sequel to The Book of Delights.) This summer I also read Wild Souls by Emma Marris and found it super thought-provoking.